The People vs Anglocentrism

What's it like to be a non-English speaker in an online world dominated by US tech bros? 🌍

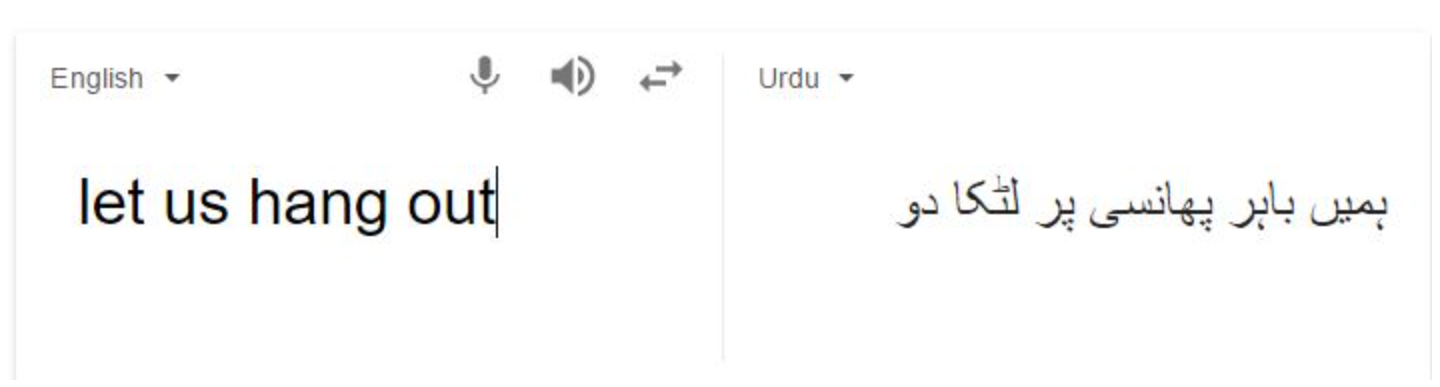

Last week, I reached out to someone on Whatsapp to schedule an interview. We ended up chatting in Urdu – the actual Urdu script, not Roman Urdu – and I realised just how unfamiliar I am typing in my native script.

I guess it’s not surprising. As so much of our phones and interfaces are in English, I rarely use Urdu online. But as my grandmother would say: these phones have ruined everything. In this case, she’s not completely wrong.

I’m Anmol Irfan, a Pakistani journalist and author of the eighth issue of The People, a bi-weekly newsletter from People vs Big Tech and the Citizens. This week, I’m looking at the dominance of the English language in Big Tech, and its far reaching implications across the globe. Through an article that is written in English. No, the irony isn’t lost on me either 🙃

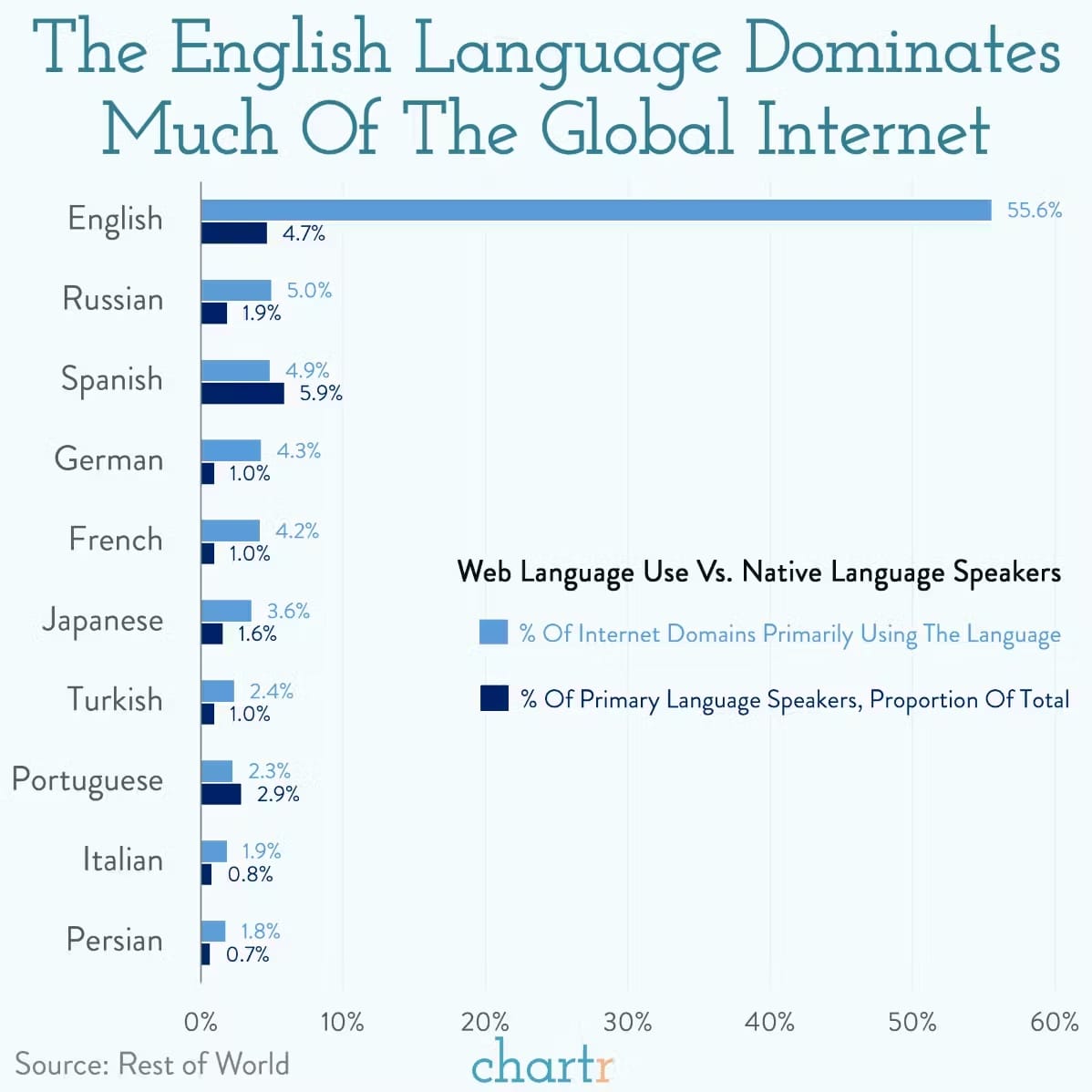

From the fading of already minoritised languages and cultures to poor moderation of non-English content on social media, Anglocentric Big Tech companies seem unable to cater for the needs of the Global Majority. Why is this – and what needs to change?

Too big to care 🤷♂️

The ‘Big Five’ Tech companies – Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet (Google), Amazon, and Meta (Facebook) – collectively earned 94 billion dollars in the last quarter of 2023 alone. Other than being incomprehensibly rich, there’s another thing they have in common: they all hail from the (majority English-speaking) US. Rasha Abdul-Rahim, interim executive director of People vs Big Tech told me:

“Time and time again research has shown that not only do Big Tech’s algorithms spread harmful content, but their content moderation systems also consistently fail in non-English speaking countries.

These companies can pursue profits over safety because they have become “too big to care”. If their monopolies were broken up, could we see the emergence of local platforms and proper content moderation by local communities in local languages? We will never know until power and control of our online world is decentralised, redistributed and democratised.”

This monopoly, then, reinforces global inequalities as many indigenous languages, and the communities which speak them, face the danger of extinction because of climate change and migration trends.

“Anglocentrism in Big Tech is an extension of the prevalent majoritarian culture – historically oppressing groups holding and hoarding socio-economic power,” Subhashish Panigrahi, a Toronto-based filmmaker and digital language activist told me.

As the expectation of having a digital presence increases in all spheres of life, those who are unable to communicate digitally are forced to live on the margins. And the technology isn’t available for many vulnerable language speakers to type in their mother tongue, added Subhashish:

“Scripts become tool of exclusion, favouring Latin and other dominant scripts, and discouraging other scripts of minoritised languages. There is less public infrastructure allocation due to lowered political representation, and lowered demand in policy.”

Zubair Torwali, a language activist from Pakistan, is a Torwali speaker – a community and minority language spoken in mountainous areas which is now under further threat due to the climate crisis. He told me that the organisation he runs has developed a Torwali keyboard for Android, supported multiple YouTube channels in Torwali, and helped develop digital dictionaries in multiple indigenous languages:

“But when I reached out to Google to get the other languages we work to preserve translated on their system online, they didn’t agree because they thought they were spoken by a small amount of people, and this is a corporate and commercialised world so they just didn’t bother with it.”

IRL impact

The exclusion of smaller languages online has all kinds of consequences. Aimee Ansari, CEO of Clear Global, a nonprofit which works to create technologies to further language preservation, told me about an issue she came across in Nigeria:

“Research said that people in North East Nigeria mostly speak Hausa, but displaced people coming in didn’t speak Hausa, and there’s close to 30 languages in the region. Because there is no information or technological support around these languages, they couldn’t access aid or assistance.”

The online dominance of Big Tech companies has a very real offline impact on safety and security across the globe. When Facebook didn’t adequately moderate content during Ethiopia’s 2020-22 Tigray conflict, particularly in terms of scaling up local language resources, posts inciting violence spread on the platform – contributing to human rights abuses.

Amnesty International released a report in 2023 which found Meta failed to adequately curb the spread of content advocating hatred and violence targeting Tigrayans during the war.

This is something I’ve noticed myself as I have seen hate speech and disinformation rising on platforms like Twitter: a lot of the problematic content I’ve come across is in Roman Urdu. Moderation algorithms don’t work so well on non-English languages, even within Europe: organisations like Global Witness have said that relying on translations to moderate content in non-English speaking EU countries is not good enough: “Moderators need a cultural and political understanding of the country they’re working on.”

“We've seen that content moderators report experiencing work-based trauma, so if companies do want to hire more moderators in marginalised and under-served languages can we please do it properly?” says EM Lewis-Jong, Director of Mozilla Common Voice. “We need to ensure this isn't farmed out as unstable gig work without proper safeguarding and psychological support,” they added.

And Big Tech’s extractive business model goes far beyond content moderation concerns. While the internet has connected people from marginalised groups and far flung regions, and has the potential to be a huge equaliser, its domination by tech giants’ toxic business model risks exacerbating inequalities and divisions instead.

There are concerns about exploitative patterns repeating themselves when it comes to the role of AI in language revitalisation, for example. While this is a promising field, Michael Running Wolf, a former engineer for Amazon’s Alexa and founder of non-profit Indigenous in AI, told CBC that there are companies and academics who want communities’ data because there's potential revenue to sell to Big Tech companies. And so, he said:

"We have to have our own engineers. We need to have our own computer scientists using the software…We need to have sovereignty over our own data, set the terms and that's the only way to build this AI."

But with current data sets and training, accurate representations of languages using AI is still a far off solution, because there are stories that only make sense in those cultures, EM told me. “Even when languages are represented in training data – say, English – the question is whose English? Not everybody's English - not Kenyan English or Singaporean English but American or British. So there’s a loss of languages but also exclusion of variants,” they say.

EM heads up Mozilla Common Voice, a platform crowdsourcing an open-source dataset of voices, with the aim of making voice-enabled technology more accessible and inclusive – rather than owned by a few companies. As they told me:

“We can’t wait for Big Tech alone to fix this problem… Putting some pressure on these companies to make linguistic diversity a priority is important – but we also need to make it very easy to do so, creating the datasets that show it's possible.”

Actions you can take ✊

- Challenge Big Tech’s monopoly. Support independent projects or start your own network of translating or documenting languages online, for example by contributing to Mozilla Common Voice.

- Use your language! If speakers of non-English languages communicate in their mother tongue as much as possible online, we can show Big Tech that other languages matter.

- Challenge the Anglocentric norm. Be open about the challenges you face using digital spaces in a language that is not your own.

People vs Big Tech is a collective of more than one hundred tech justice organisations around the world. This means we put together each newsletter with the help of the smartest and most respected experts in this field.

Email bigtechstories@the-citizens.com if you have an idea for a Big Tech issue you'd like us to cover.