The People vs TikTok Brain

Are we melting our brains by scrolling on endless short videos? 🫠

Archaeologists look at burial grounds to search for answers about the human condition. I look at the TikTok search bar.

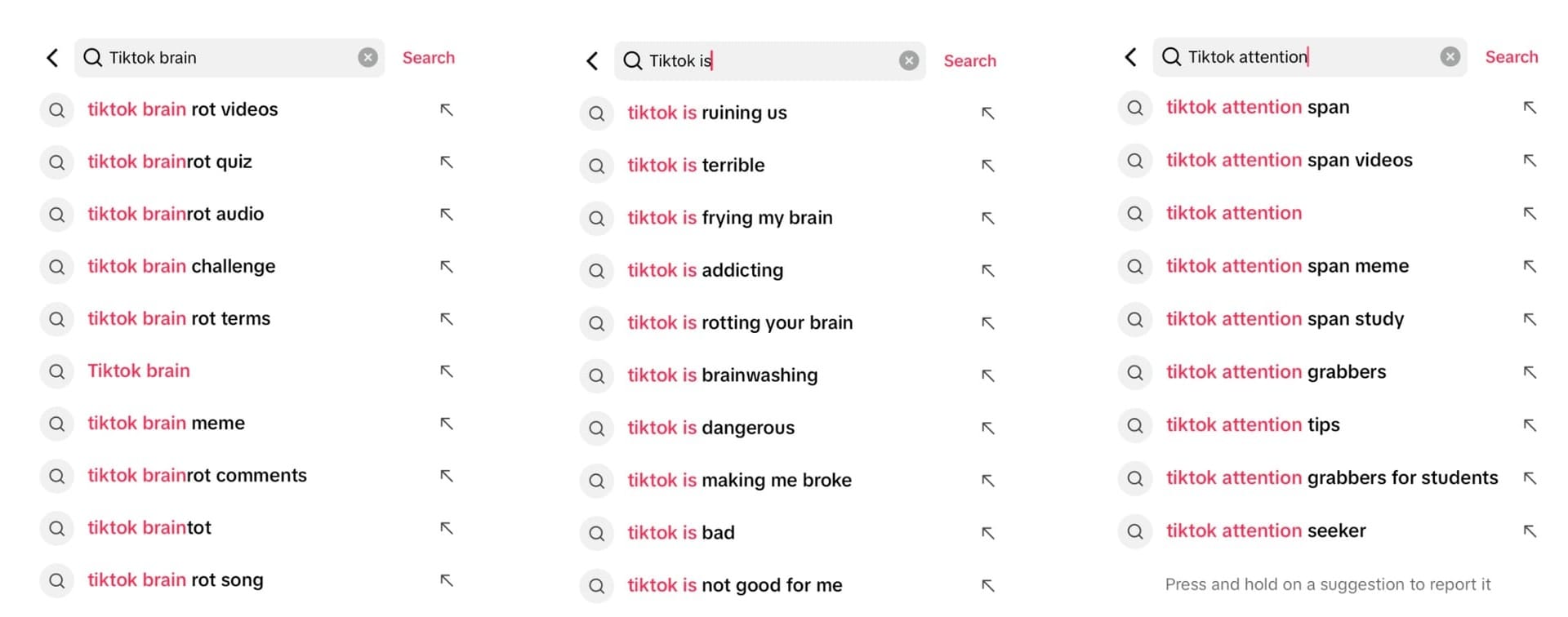

When I type in ‘TikTok’ and ‘brain’, it shows suggestions based on what others had searched before me. “TikTok brainrot” queried one person. “TikTok is ruining us” wrote another. “TikTok ruined my attention span” and “TikTok is brainwashing people” popped up too.

Just as ancient sites tell us about what was once important to people, the search bar tells us some of our greatest anxieties and questions today. It is clear that users are not searching TikTok’s archives to enlarge their brains - but to save them.

I’m Sophia Smith Galer, a journalist, TikTok content creator and author of the sixth issue of The People, a bi-weekly newsletter from People vs Big Tech and the Citizens. I’m exploring TikTok brain: a term coined in a widely cited Wall Street Journal article about the effect endless short videos on social media are having on our grey matter 🧠

In the piece, journalist Julie Jargon describes a phenomenon parents spoke to her about. How their kids “can’t sit through feature-length films anymore because to them the movies feel painfully slow” and how “others have observed their kids struggling to focus on homework. And reading a book? Forget about it.”

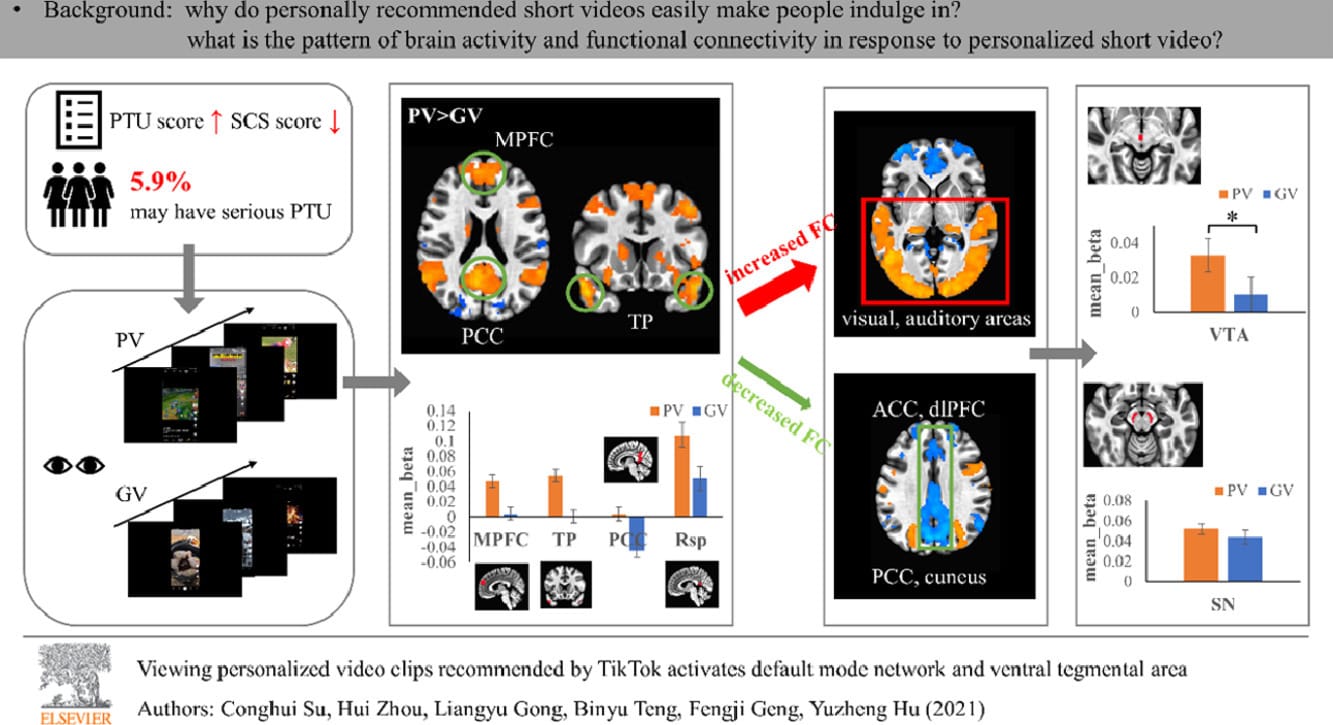

Jargon references an alarming study on Douyin, the TikTok equivalent in China, where brain scans revealed that the college students using the app showed high activity in the part of the brain associated with addiction when they watched videos personalised to them.

While overuse of social media is not currently defined as a disorder, we know that all the platforms (definitely not just TikTok) are addictive by design and for many of us, this is affecting our mental health. Many experts are particularly concerned about the impact on the minds of children.

You might enjoy how the algorithm shows you exactly the kind of stuff you like. But is our scrolling doing us more harm than good?

A love hate relationship

There are wonderful positives to get from the internet. In an international study from the University of Oxford this year 84.9% of associations between internet connectivity and wellbeing were positive.

TikTok, for many of us, is part of that joy. Me included: hours of social media a day has helped me learn something new everyday, share my reporting and ideas with hundreds of thousands of people, and even get jobs.

But for many, particularly young people growing up with social media, the effects are toxic. TikTok overuse has been linked to memory loss, depression, stress and anxiety, as well as neuroticism.

The impact of this can be devastating. The coroner for the inquest for Molly Russell, the British teenager who tragically took her own life in 2017, said social media contributed “more than minimally” to her death.

Internet/gaming addiction, language development, and the processing of emotional signals have been observed by some neuroscientists seeking to understand the impact of the digital revolution on the brain. And one study looked at a bizarre phenomenon of teenagers developing Tourette syndrome after watching hours of videos on TikTok about the condition.

Of course, it's not just TikTok. On top of their own addictive features, other Big Tech companies have copied the Chinese app’s endless scrolling video format. After TikTok was banned in India, for example, YouTube Shorts launched in the country, engaging users in what one study described as "short bursts of thrills" which can lead to addictive behaviour.

According to author of Dopamine Nation and psychiatrist Dr Anna Lembke, the difference between social media overuse and other addictions is that there are no limitations forcing us to pause. While you run out of money for cocaine or a slot machine, social media feeds just keep loading regardless. This affects our attention spans, she told The Guardian, and keeps us in our emotional limbic brain rather than our prefrontal cortex, which plays a key role in executive function and cognition.

But Lembke admits her theory is inferred from studies of stimulant drugs: there isn’t evidence to back it up for social media addiction yet. Neurologist Martin Kote also argues datasets beyond self-reported parameters “with higher precision in terms of what is done on screens, for how long, and at what age” are needed.

Bernadka Dubicka, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at Hull York Medical School, told me researchers need tech company data in order to adequately measure the mental health impact of the platforms. For now though, she says:

“There is evidence that girls may be more negatively affected due to the impact of social comparisons and impact on self-esteem…Other important factors to consider are a young person's environment, how supported they are, and whether they have a healthy balanced lifestyle.”

This puts vulnerable children at most risk - such as those in care and living with disabilities - although conversely, many such young people also rely on digital connection.

Some research makes this point. Social media has increased our ability to “effortlessly communicate with peers” and helped some of us access identity-affirming content related to intersections such as gender, sexuality and race.

Getting healthy 🥦🥦

We don’t need there to be a clinical disorder for us to comprehend that for some, social media use is harmful. Unfortunately, the business model of platforms like TikTok and Instagram is to keep us within the app for the longest amount of time possible to attract advertising spend.

I spoke to Victory Brown, a researcher at Superbloom, a non profit operating at the intersection of digital design and human rights. She describes autoscroll as a feature that “causes more harm than good,” explaining that:

“What leads to this addiction is the algorithm…it will keep bringing content similar to whatever you interact with the most, and if this is your interests and likes, you could spend hours mindlessly scrolling.”

Social media expert Matt Navarra points out features like this remove “any decision points, encouraging passive consumption” and that the unpredictable pattern of rewards keeps you scrolling and in repetitive loops similar to gambling.

In October 2023, dozens of US states filed a lawsuit on behalf of young people accusing Meta of deliberately designing features that addict children to its platforms, leading to "depression, anxiety, insomnia, interference with education and daily life". Facebook has even done its own research: in 2021 its company documents showed a significant teen mental health issue on Instagram that was played down publicly.

But Matt is sceptical that Big Tech can be persuaded to change their features (such as addictive design) because they keep ad money flowing in. He suggests platforms find alternative revenue models to reduce their reliance on advertising, like subscriptions. Regulation can add pressure with standards, he told me, but “they also have to be enforced and the punishments have to be strong enough to incentivise these platforms to change.”

There are glimmers of hope. In June, New York signed two state laws which could limit “addictive feeds” for users under 18 as well as reeling in the collection of children’s data. There’s also the EU’s 2022 Digital Services Act which forces Big Tech platforms to assess the risks their business models have on users' rights, particularly young people. If enforced, it could also force these companies to modify their interfaces and content ranking algorithms.

The EU Parliament is pushing for lawmakers to go even further. Last December, a majority voted to propose new measures that would "assess and prohibit the most harmful addictive practices" - that could include things like auto-play and infinite scroll features.

Social media could play a far healthier role, particularly for the most vulnerable in society, many of whom feel stuck in an ouroboros of content where there’s no way out of a scrolling experience that leaves them ill-informed, and under-supported.

But for now, social media platforms still don’t see a competitive advantage, or regulatory pressure, that has been convincing enough to alter design features that are likely detrimental to our health.

Actions you can take ✊

- Worried you’ve got TikTok Brain? Franziska Benning at Hate Aid suggests you reset your For You Page, and add screen time limits to control your doom-scrolling. On Insta, reset your Explore Page by clearing your search history.

- Join The Guardian’s five-week expert coaching plan to help you reset your screen habits. They say participants have cut their screen time by 40%.

- Sign Global Action Plan’s petition to protect children’s mental health and make social media safe by design.

People Vs Big Tech is a collective of more than one hundred tech justice organisations around the world. This means we’re putting together each newsletter with the help of some of the planet’s smartest and most respected experts in this field. Email bigtechstories@the-citizens.com if you have an idea for a Big Tech issue you'd like us to cover.